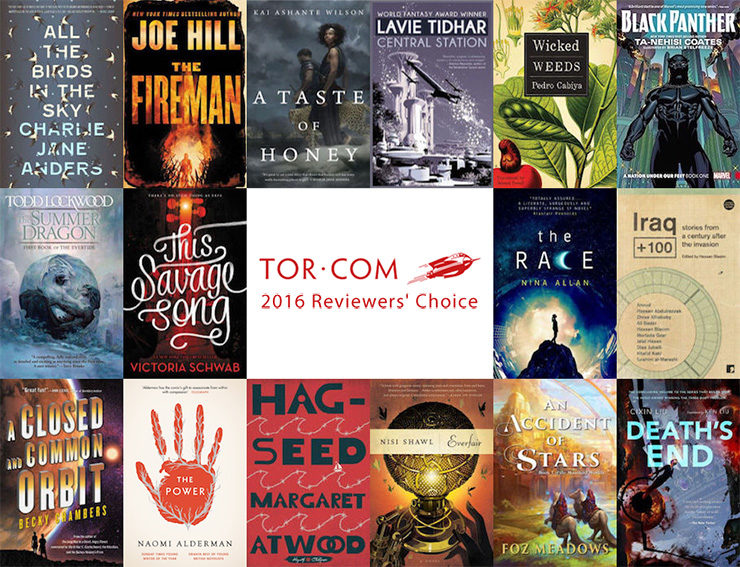

Other than action figures, mugs of tea (Earl Grey, hot), and glorious unicorn lamps, the sight most prevalent in our offices rocket ship here at Tor.com are heaps and heaps of books!

Between our rereads of everything from Dune to the The Wheel of Time, and our regular bookish columns—Five Books About…, That Was Awesome!, Sleeps with Monsters, our comics Pull List, and Genre in the Mainstream, to name a few—we’re reading books and reviewing books around the clock! So with 2016 coming to a close, we invited some of our regular contributors to choose their three favorite books from the last year, and we’re sharing their responses and recommendations below. Please enjoy this eclectic overview of some of our favorite books from the past year, and be sure to let us know about your own favorites in the comments!

Mahvesh Murad

I know I had Margaret Atwood in my list for 2015 too, but how can I not have her in my list for 2016? This was the year I spoke with her about her work, which made her last novel, Hag-seed, so much more fun to read. A reimagining (of sorts) of The Tempest, Atwood sets her story in a prison (not the sort she set The Heart Goes Last in, but a standard modern day one), where a theatre director who has been forced into retirement eventually emerges, older but not tamer and teaches the inmates at the local prison literacy through Shakespeare. Ultimately though, he’s using this as a way to get his own back to those who slighted him. Hagseed is full of Atwood’s spiky, shiny brilliance—it’s funny and smart and of course it’s oh so tender.

I know I had Margaret Atwood in my list for 2015 too, but how can I not have her in my list for 2016? This was the year I spoke with her about her work, which made her last novel, Hag-seed, so much more fun to read. A reimagining (of sorts) of The Tempest, Atwood sets her story in a prison (not the sort she set The Heart Goes Last in, but a standard modern day one), where a theatre director who has been forced into retirement eventually emerges, older but not tamer and teaches the inmates at the local prison literacy through Shakespeare. Ultimately though, he’s using this as a way to get his own back to those who slighted him. Hagseed is full of Atwood’s spiky, shiny brilliance—it’s funny and smart and of course it’s oh so tender.

A writer who worked with Atwood for her newest novel is Naomi Alderman, whose The Power left me amazed and horrified in the best of ways. I’ve been calling it the wild godchild of Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale and Rukaiya Hossain’s The Sultana’s Dream, and it is this and much more. In a world where women have the physical ability to electrocute anyone or anything at will, what happens to power balances between genders? What happens to the gender biases in current societal conflict, in politics, in family life? Why do we assume that if women have brute strength, they wont use it to gain absolute power, and that absolute power won’t corrupt them? It’s a shocking book, not because if the actions of the women, but because it forces you to analyse your own gender based assumptions about women—even if you yourself are one.

Another book about what makes someone a monster and who gets to decide is Victoria Schwab’s This Savage Song, which has more to it than it’s a fantastic title. In a world where every act of violence creates an actual physical monster, two young people are trying to figure out who they are, what others need them to be and what they are afraid to become. Given the amount of xenophobia in the world right now, this YA novel is so perfectly apt that it hurts.

Emily Nordling

2016 has been a good year for civil unrest, and the literary landscape is no exception. Ursula Le Guin’s revolutionary worlds made a valiant return in release after re-release. Her novel, Malafrena, is one of my favorites of the lot, as it explores the hazy boundaries of the personal and the political (something I imagine we can all relate to as the Holiday season approaches).

2016 has been a good year for civil unrest, and the literary landscape is no exception. Ursula Le Guin’s revolutionary worlds made a valiant return in release after re-release. Her novel, Malafrena, is one of my favorites of the lot, as it explores the hazy boundaries of the personal and the political (something I imagine we can all relate to as the Holiday season approaches).

Another piece of historical fiction that fits the bill is Alexander Chee’s Queen of the Night, about a legendary soprano at the Paris Opera. Set amidst the decadence of the Second Empire, Chee’s brilliant novel explores memory, freedom, and every combination thereof, as the characters move with painful deliberation towards the revolution of 1871.

And finally, for a more modern spin, Ta-Nehisi Coates’ new run of Black Panther is everything I wanted out of a comic this year. Like the other books I’ve mentioned, its message is change, with T’Challa struggling to rule a kingdom that is transforming from the inside-out. Gorgeously illustrated and utterly riveting, this is the book out of all of these that I hope to carry like a weapon into 2017.

Less (explicitly) revolutionary but still excellent: Charlie Jane Anders’ All The Birds in the Sky, Maggie Stiefvater’s The Raven King, and Vol. 3-4 of Gillen and McKelvie’s The Wicked + The Divine.

Jared Shurin

Well, 2016 sucked. But at least we got some good books out of it.

Well, 2016 sucked. But at least we got some good books out of it.

In Jenni Fagan’s The Sunlight Pilgrims, ordinary people are quietly trying to get on with life as the snow falls around them. Forever. Like her gorgeous debut, The Panopticon, Fagan’s ability to highlight the extraordinary buried in the everyday is on full display, as is her glorious use of language. A heart-breaking saga of small triumphs against an apocalyptic background.

Becky Chambers’ A Closed and Common Orbit features an AI trying to find her place in the world, aided by an escaped clone who has built her own identity from scratch. A novel that examines both self-determination and friendship, Orbit is about the life we choose, and the people we choose to fill it with. Chambers is simply an exceptional talent, quietly and beautifully redefining the space opera.

Erin Lindsey’s The Bloodsworn concludes one of my favourite fantasy series. The trilogy is exciting from start to finish: it starts with a desperate charge into a battle and never loses its momentum. The story contains all the best of romance, warfare, magic and political scheming; all glued together by a cast of warm and wonderful characters.

Alex Brown

2016 was a great year for diverse and oddball SFF. I absolutely loved Zoraida Córdova’s Labyrinth Lost. Months later and I am still haunted by resilient Harper from Joe Hill’s The Fireman. Kim & Kim, Black Panther, The Backstagers, and Spell on Wheels are rewriting the “rules” of comic books by playing exciting new games in an old, well-worn sandbox. While not exactly diverse but certainly unique and off the wall, Drew Magary’s searing The Hike and Ian Tregillis’ cracking forthcoming finale to the Alchemy Wars trilogy, The Liberation, are definitely in my top 10.

2016 was a great year for diverse and oddball SFF. I absolutely loved Zoraida Córdova’s Labyrinth Lost. Months later and I am still haunted by resilient Harper from Joe Hill’s The Fireman. Kim & Kim, Black Panther, The Backstagers, and Spell on Wheels are rewriting the “rules” of comic books by playing exciting new games in an old, well-worn sandbox. While not exactly diverse but certainly unique and off the wall, Drew Magary’s searing The Hike and Ian Tregillis’ cracking forthcoming finale to the Alchemy Wars trilogy, The Liberation, are definitely in my top 10.

But my favorites of the past year have to be Conspiracy of Ravens, the second book in the Shadow series by Lila Bowen, and Lovecraft Country by Matt Ruff. The former is a Weird West YA fantasy about a queer Black trans teenage cowboy shapeshifter named Rhett who takes on an ancient god, a wicked circus witch, and a railroad baron warlock. The latter tells interconnected stories about a Black family in the 1950s as they deal with the descendants of the white men who owned their ancestors and the chthonic magic they wield in an attempt to subjugate them. Both are books I’ve recommended to nearly everyone I know, they’re that good.

Martin Cahill

All The Birds In The Sky by Charlie Jane Anders: This was one of the first books I read this year, and it certainly set the bar high. A chimera of a novel, Anders throws everything and the kitchen sink into this stunning story of two people from two different worlds becoming friends, falling out, and finding each other again as the world goes to hell. Both lonely and often ignored in their youth, Patricia and Laurence find each other, and though their burgeoning adulthoods thrust them into worlds of magic and science respectively, they find each other again in their mid-twenties, each in their own way trying to save a planet that is quickly dying. Anders’ examination of these two complicated individuals, their iron-clad worldviews, their friction and their feelings for each other, is engrossing in all the right ways. Patricia and Laurence don’t always make the right decisions, and as in life, sometimes they hurt each other very deeply. But their commitment to helping each other no matter what, for not giving up on compassion and kindness in the face of disaster and pain, makes this novel a very worthy read.

All The Birds In The Sky by Charlie Jane Anders: This was one of the first books I read this year, and it certainly set the bar high. A chimera of a novel, Anders throws everything and the kitchen sink into this stunning story of two people from two different worlds becoming friends, falling out, and finding each other again as the world goes to hell. Both lonely and often ignored in their youth, Patricia and Laurence find each other, and though their burgeoning adulthoods thrust them into worlds of magic and science respectively, they find each other again in their mid-twenties, each in their own way trying to save a planet that is quickly dying. Anders’ examination of these two complicated individuals, their iron-clad worldviews, their friction and their feelings for each other, is engrossing in all the right ways. Patricia and Laurence don’t always make the right decisions, and as in life, sometimes they hurt each other very deeply. But their commitment to helping each other no matter what, for not giving up on compassion and kindness in the face of disaster and pain, makes this novel a very worthy read.

Too Like The Lightning by Ada Palmer: There are many novels that blow you out of the water, that set their stake in the ground of your heart and make you declare, “Yes! This! This is what ____ could be!” Well, for me, that novel is Ada Palmer’s debut, Too Like The Lightning, I say it will be my definitive go-to novel when someone asks me, “What could science fiction be?” A dense, complicated, gorgeous novel set in the year 2454, Palmer’s debut has many threads, but the main line is tethered to a man named Mycroft Canner, a Servicer dedicating his life to helping others in the wake of his crimes. While serving the upper echelon of leaders, diplomats, sadists, and soldiers, Canner is also taking care of a special young man named Bridger, whose abilities are unseen in this utopian world. But this is only one small slice of the story that Palmer is telling. Along the way, there are mysteries of law, of faith, of society, of family, and more, as she weaves a fractal narrative that rockets forward, tighening in on itself with every chapter. Her vision of the international melange our world could become, of the technology we could conceive of, of the dreams we could attain are perfectly balanced against the baroque language of our past, the desperately modern current running through each thread, and ultimately, the base human motivations that no matter how we evolve, will never go away. It is an astonishing debut, and I cannot wait for the sequel out in 2017.

The Fisherman by John Langan: Truly great horror stories make you question your own world; after being submerged in a world of dark water, how can you tell if the world you’ve returned to is really yours? Just how far away does that dark water lurk, and how easily can you slip into it? John Langan’s The Fisherman will gift you that intense unease; it will also set its hooks into you, and pull you into its depths with meditations on life, death, worth, fear, the unknown, and make you ask: what would you give up to get back the person you loved the most? Two widowers, Abe and Dan, are drawn to a long forgotten creek in Upstate NY to fish, a practice they took up in the wake of heart-wrenching death: Abe’s wife lost to cancer, Dan’s family lost to a car accident. But on the way, they learn the true story of Dutchmen’s Creek, and of the Fisherman who used to lurk near its waters, who cast not for fish, but for something grander, something terrible and monstrous. Langan’s novel is deliberate, elegant, and beautifully written; the horror and trauma of these two men is explored to the bone, and in the end, knowing them so well only makes the horrors to come that much more terrifying. If you enjoy horror, I’d highly recommend this incredible novel.

Liz Bourke

Every year, when the Tor.com Reviewer Choice question comes around, I complain that making a choice is an exercise in frustration. (It really is.) This year, it’s just as frustrating as ever. I still can’t pick a best book, but I can pick a couple of favourites.

Every year, when the Tor.com Reviewer Choice question comes around, I complain that making a choice is an exercise in frustration. (It really is.) This year, it’s just as frustrating as ever. I still can’t pick a best book, but I can pick a couple of favourites.

Foz Meadows’ An Accident of Stars is far and away my favourite novel of the year (despite the mess Angry Robot Books made of the formatting). A fantastic portal fantasy with an amazing cast of characters, it’s the kind of book I wish I could read more often. Heroism, desperation, politics, family (found and blood), choices, consequences, shiny magic, badass worldbuilding: it has everything you could desire.

I don’t know how to talk about Yoon Ha Lee’s Ninefox Gambit. It’s so good and so twisty and so brilliant and so mind-explodingly full of intensely science-fictional batshit worldbuilding and excellent characters—and so relentlessly, brutally, full of massacre and killing and atrocity that I don’t quite know whether I love it or hate it. But I have to recommend it.

I can’t make up my mind what else is best. (Better than all the rest.) Between Nisi Shawl’s amazing Everfair and Ada Palmer’s scintillating Too Like The Lightning, Marie Brennan’s Cold-Forged Flame and Kai Ashante Wilson’s A Taste of Honey, Django Wexler’s The Guns of Empire and Fran Wilde’s Cloudbound, how am I supposed to choose?

Tobias Carroll

Helen Oyeyemi’s fiction brings together centuries-old narrative structures with urgent questions about race, gender, and identity that tap into deeply contemporary concerns. Some of the pleasure of reading her work comes from the unpredictable ways in which the stories she tells unfold. Her new collection, What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours, finds her bringing that kind of convergence to the shorter form–and showing off her more experimental side along the way.

Helen Oyeyemi’s fiction brings together centuries-old narrative structures with urgent questions about race, gender, and identity that tap into deeply contemporary concerns. Some of the pleasure of reading her work comes from the unpredictable ways in which the stories she tells unfold. Her new collection, What Is Not Yours Is Not Yours, finds her bringing that kind of convergence to the shorter form–and showing off her more experimental side along the way.

Colin Dickey’s Ghostland follows from his earlier works of nonfiction, which frequently delve into obscure histories and tales of obsession. Here, his focus is on haunted places and local tales of ghosts, which frequently turn out to hide bleaker histories that are much more frightening than apparitions in the night or strange images at the corner of one’s eye–tales of hate crimes, institutional racism and sexism, and moments that tear at the edges of history all come to mind.

It’s also been a great year for surreal stories that both explore new worlds and do unexpected things with language, structure, and style along the way. Matt Bell’s A Tree or a Person or a Wall and Amber Sparks’s The Unfinished World and Other Stories both fall into this category, telling stories of surreal visitations, obsessions, and moments when the nature of reality becomes decidedly ambiguous. They’re memorable and haunting in equal measure.

Niall Alexander

I had to be markedly more selective in my reading in 2016, so picking just a few of the eighty-odd very good books I cleared this year has been evil. Times like these, though, I guess you’ve got to be merciless, so of all the science fiction and fantasy I’ve sucked up since last we did this thing, I’ve landed on some stand-outs.

I had to be markedly more selective in my reading in 2016, so picking just a few of the eighty-odd very good books I cleared this year has been evil. Times like these, though, I guess you’ve got to be merciless, so of all the science fiction and fantasy I’ve sucked up since last we did this thing, I’ve landed on some stand-outs.

The history of Howard Falcon, that ambassador between man and machine introduced in Arthur C. Clarke’s “last significant work of short fiction,” was extended with expected spectacle but also surprising sensitivity by Stephen Baxter and Alasdair Reynolds in The Medusa Chronicles: a nicely-handle narrative that had me near to tears. Central Station by Lavie Tidhar rewrote the rules of the short story collection to unforgettable effect by seamlessly soldering together thirteen disparate windows into the lives of the disaffected folks who live at the base of the titular spaceport. And although I practically vibrate with hatred at the merest mention of greyhound racing, Nina Allan managed to make me care about the smartdog society she created in The Race, a text so very revelatory that I’ll read anything its author has a hand in from here on out.

But I’ve saved the best for last, haven’t I? I have! My no bull book of the year—and this reviewer’s choice—has to be A City Dreaming. As debauched as it is divine and as drug-addled as it is dreamy, this assemblage of loosely-connected vignettes is quite simply the best thing Daniel Polansky has ever written—and between the Low Town trilogy, The Builders, Those Above and Those Below, he’s already written some brilliant things. If you haven’t read him yet—if you haven’t read A City Dreaming, even—then I’m sorry, but you’re doing it all wrong.

Rachel Cordasco

It’s been an outstanding year for world sf: we’ve had books about Caribbean zombies and alternate universes, gigantic alien amoebae and literary polar bears, not to mention cyborg turtles and the end of the universe itself. Therefore, it’s difficult to choose just three, but here are my favorites from 2016:

It’s been an outstanding year for world sf: we’ve had books about Caribbean zombies and alternate universes, gigantic alien amoebae and literary polar bears, not to mention cyborg turtles and the end of the universe itself. Therefore, it’s difficult to choose just three, but here are my favorites from 2016:

Wicked Weeds by Pedro Cabiya, translated by Jessica Powell: This multifaceted, playful, and chilling novel out of the Dominican Republic is both about and not about zombies. Through scrapbook fragments and first-person narration, we learn about a “gentleman zombie” who uses his position at a pharmaceutical research lab to try to figure out how to bring himself “back to life.” According to the zombie, he and those like him are just barely able to pass as “normal” human beings, but they are always fearful of inevitable decomposition and a resulting backlash from friends and coworkers. Cabiya takes us on a unique journey of zombie discovery, inviting us to think about how these beings have evolved in the popular imagination across time and geography. You’ll laugh out loud, your spine will tingle, and you’ll come away convinced of this book’s brilliance.

Death’s End by Cixin Liu, translated by Ken Liu: In case you missed my many enthusiastic reviews of this third and final installment in the Three-Body trilogy, I’ll repeat: this book will twist your brain into a pretzel in the best way possible. In Death’s End, we witness the brief triumph of the Trisolarans over humanity and the inevitable occurrences that are the product of a universe that functions like a “dark forest” (where civilizations destroy one another because every one is a potential threat). In densely-lyrical prose, brilliantly translated by Ken Liu, we are swept up into increasingly vast questions and situations, through the end of the solar system, the universe, and beyond. This is hard science fiction at its best, and I plan to reread the trilogy because it’s that good.

Iraq + 100: Stories From a Century After the Invasion, ed. Hassan Blasim: As Blasim notes in his introduction to this remarkable collection, Iraqi writers haven’t exactly been churning out the speculative fiction over the past decade. They’ve had other things to worry about, like the invasion and destruction of their country. Plus, the genre is often given short shrift by higher-ups in the literary establishment. Thanks to Blasim and Comma Press, though, we now have this collection of speculative fiction by Iraqis about what Iraq might look like 100 years after the invasion of 2003. Self-aware statues, (literally) blood-thirsty alien invaders, and tiger-droids are just some of the things you’ll come across here, and the ways in which certain writers turn aggression, invasion, and resistance on their heads will will leave you questioning some of your core assumptions about the world beyond our borders. This collection is important for many reasons, and hopefully we’ll have many more in the future.

Rob H. Bedford

2016 has come and is on its way out and like all years, some excellent Speculative Fiction books published. Narrowing this down to three is a difficult task, but here it goes. Joe Hill has consistently published supremely engaging fiction regardless of the medium, his fourth novel The Fireman was a standout in 2016. The Fireman is his biggest novel and as a post-apocalyptic tale (the obvious comparison to Papa King’s The Stand is blatant, but also warranted on quality alone), it is his widest in scope. What is so remarkable is that for such an expansive novel, it might also be Joe’s most intimate.

2016 has come and is on its way out and like all years, some excellent Speculative Fiction books published. Narrowing this down to three is a difficult task, but here it goes. Joe Hill has consistently published supremely engaging fiction regardless of the medium, his fourth novel The Fireman was a standout in 2016. The Fireman is his biggest novel and as a post-apocalyptic tale (the obvious comparison to Papa King’s The Stand is blatant, but also warranted on quality alone), it is his widest in scope. What is so remarkable is that for such an expansive novel, it might also be Joe’s most intimate.

A novel that really surprised me was Todd Lockwood’s The Summer Dragon. Lockwood is more famous for his powerful, fantastical images – especially his dragons. The Summer Dragon has all the hallmarks of classic, secondary world fantasy: youthful protagonist, magic and fantastic creatures, and a deep, richly detailed world with a long history. Those elements are a cohesive whole when woven together with Mr. Lockwood’s wonderful storytelling. It is very clear Todd Lockwood has a love of the fantastic and where he could have easily just created a slavish homage to the Epic Fantasy of the past couple of decades, he imbues the tale with a great deal of heart and modern sensibilities.

Perhaps the most naturally and perfectly told novel I read in 2016, Sarah Beth Durst’s The Queen of the Blood. The bones of the story are relatively straight-forward, but what Durst does with the framework is very powerful, evocative and quite simply, elegant. Queen of the Blood upends gender expectations. Much of epic fantasy that focuses on a youthful, “chosen one” protagonist focus on a young man, not so here in Queen of the Blood and features only one male primary character, and a couple of supporting male characters. While I suspect this was very much intentional on Durst’s part, nothing about it felt forced or shoe-horned. It was a lovely, powerful novel.

Honorable Mentions: City of Blades by Robert Jackson Bennett; A Gathering of Shadows by V.E. Schwab; Seanan McGuire’s Every Heart a Doorway; and two novels from previous years making their US print debut in 2016: The Copper Promise by Jen Williams and The Long Way to a Small, Angry Planet by Becky Chambers.

Theresa DeLucci

I read way more anthologies this year than full-length novels; horror and the Weird seem to work best at a shorter length for maximum impact. It was extremely tough to pick a favorite single-author collection. I seriously went back-and-forth on my pick several times. This year saw hotly-anticipated collections from genre heavies Laird Barron, Brian Evenson, and Jeffrey Ford, as well as a stellar debut collection from newcomer Michael Wehunt. But I think the collection that most stayed with me—I read it back in January—was Livia Llewellyn’s Furnace and Other Stories. Vicious, beautiful, and darkly erotic, these stories got under my skin in the best possible way.

I read way more anthologies this year than full-length novels; horror and the Weird seem to work best at a shorter length for maximum impact. It was extremely tough to pick a favorite single-author collection. I seriously went back-and-forth on my pick several times. This year saw hotly-anticipated collections from genre heavies Laird Barron, Brian Evenson, and Jeffrey Ford, as well as a stellar debut collection from newcomer Michael Wehunt. But I think the collection that most stayed with me—I read it back in January—was Livia Llewellyn’s Furnace and Other Stories. Vicious, beautiful, and darkly erotic, these stories got under my skin in the best possible way.

My choice for best novel of 2016 was easy: Stephen Graham Jones’ werewolf coming-of-age story, Mongrels. It had me from its eye-catching yellow cover to its afterword note about the author’s love for Southern-fried vampire movie Near Dark. Werewolves aren’t as sexy as vampires and Jones doesn’t try to make them be, instead imagining in clever physiological detail the challenges only werewolves would face in America. Seen through the eyes of a young boy desperately, impatiently, waiting to see if he’s been born with his family’s curse, Mongrels is just as much about puberty as it is about class; The Outsiders with teeth. It’s gorgeously written and heartbreaking and I can’t recommend it enough.

Lastly, I loved Victor LaValle’s The Ballad of Black Tom. I read a lot, too much, in the Lovecraft-inspired vein, and LaValle’s searing take on the grandmaster of horror hit like a punch to the gut. A tribute and a takedown, Harlem hustler Tommy Tester traverses 1920s New York City and stares into the face of a cosmic horror. But the real terror comes from human indifference, as police brutality and racism collide with devastating, horrifying consequence. This story, too, haunted me all year and is very likely the golden standard of Lovecraft revision.